Stranded in an alien

land and cut off from his family’s fortune, he sought every opportunity

to make a living. By May 1918, he was permanently settled in Manhattan

and already was accepting commissions for portraits. He solicited letters

of recommendation from high-ranking Russian émigrés and

used these contacts to find employment. In 1919, he took a job in a factory

in Saint Louis, Missouri, and letters to Olga speak of his sadness at

having no time to paint. In an especially poignant passage, he tells of

walking to the pavilion (now The Saint Louis Art Museum) where his graduation

painting had hung in 1904.

He returned to Manhattan by 1920 and began to have some commercial success. From the moment of his exile in America, Djeneeff drew on skills acquired through a lifetime of artistic activity bolstered by formal training at the Academy. His interest in depicting old Russian and Slavic stories led to contracts for book illustrations; his abilities as a draftsman brought commissions for banknotes (destined for anti-Bolshevik forces in Russia) and advertising contracts with prominent American companies. His restoration work at Kostroma gave him the credentials to solicit business from important galleries; and his extensive experience as a portrait painter resulted in numerous commissions for large-scale and miniature paintings. Djeneeff’s good nature and ease in establishing relationships with others led to orders for commercial artworks from Russian émigré societies. As had always been the case with his art, Djeneeff was a believer in the importance of details, and this quality now served him in exile.

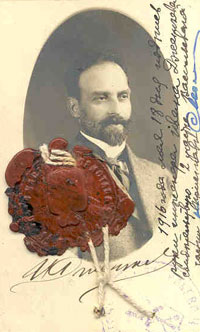

Ivan Djeneeff, passport (1916)